When you’re researching something from history you need to be a little bit careful. Usually you’re dealing with scraps of information almost as if you’re trying to interpret events from what appear to be punctuation marks in the life of your subject with all of the sentences in between missing. Occasionally whoever created that information may well have placed it incorrectly or used the wrong one.

I have to confess to having tripped up a few times along the way with researching the Wizard and the Typhoon. However I’m lucky, and grateful, to be part of a team that will question my assertions from time to time. Our Australian Patron, a fine researcher in his own right, Eric Tomkins, is happy to intervene, as is my colleague and friend Brian Yates here in England.

How is it that we go so wrong sometimes?

Let me give an example. The past three months have been a tricky one for me in terms of researching George Allan and Thomas Bulch. Sometimes work, as in the ‘day job’, gets a little busy and between that and other commitments I don’t get the time I’d like to spend on this project. One morning however I thought I’d try a little random ‘fishing’ among old newspaper articles and I was surprised to find this little article on the Trove site.

It’s always nice to find another reference to “Opossum Hunt”, “Antipodes” or “Sandhurst”; or even “Craigielee” (however mis-spelled) or “Bonnie Jeanie Grey” by Bulch’s pseudonym Godfrey Parker but what really caught my eye was the title “Whitworth” which is attributed here to Bulch.

Now had this been a piece by “Allan” I’d have immediately been recalling the usual question that Brian would level at me which runs along the lines of “Are you sure it’s our Allan – George Allan?”

Quite rightly, Brian is only ever entirely sure when he’s seen the music, and seen either the “2 Pears Terrace” or “4 Osborne Terrace” address on it.

But, I thought to myself, this says “Bulch” and in 1892, to the best of my knowledge and with it being such a rare surname, in the world of Australian brass banding there is only one Bulch and that’s Thomas Edward Bulch. This looked very much like an as yet undiscovered title of another Bulch march. Fantastic! Furthermore, to me, and anyone who knows the area where Thomas Edward Bulch was born the name “Whitworth” has tremendous significance. Less than ten miles away from New Shildon is the estate of Whitworth, the ancestral home of the Shafto family, the most famous of which was Robert “Bobby” Shafto about which an extremely popular song of the North East was written.

“Bobby Shafto’s gone to sea, Silver buckles on his knee, He’ll come back and marry me, Bonny Bobby Shafto.”

Knowing that Thomas Bulch composed before he left the region of his birth, in my mind, already (and less than an hour later, literally) I was adding “Whitworth’ to a map of locally titled marches by George Allan and Thomas Bulch – placing it alongside Bulch’s “Shildon” and Allan’s “Windlestone”, “Binchester” but not going so far away as Allan’s “Belmont”.

I had had my fingers burned in the past for having presumed that Bulch’s march “Newcastle” might have been a reminiscence of his best English brass band contest result with the New Shildon Temperance Band when he conducted his band to second place at a band contest in Newcastle, England (probably the region’s most significant city economically, if not in footballing terms); only to discover unquestionably (through textual evidence) from Eric Tomkins and Bob Pattie that the piece was actually a tribute to W. Barkel, a prominent bandmaster of Newcastle, New South wales Australia. Eric reminded me of this, only this week, having spotted an old Tweet where i was wondering which Newcastle it was. So, I thought a quick geographic check of Victoria etc was in order. No places called Whitworth in Victoria or any of the other Australian states – though there was a somewhat unremarkable Whitworth Ave. in Melbourne; a residential street that didn’t look to be much cause for celebration in march form.

That alone should have proved a warning to me though. But, sometimes, you see something, formulate your hypothesis, and it seems to make so much sense to you that you want it, deeply want it, to be true. Had I paused for a moment to dig a bit deeper I may not have tripped myself up by my enthusiasm for my own theory. I should not be so surprised to find my theory to be fatally flawed.

One of the things that I finds so utterly brilliant about the overall story of Thomas Bulch and George Allan is that in the late nineteenth century, a world which we consider retrospectively to be utterly ‘un-connected’, in the modern sense, was actually remarkably joined up in surprising ways enabling all kinds of remarkable coincidences through the repetition of names and places. Consider the following:

- Thomas Bulch left Adelaide Street in Shildon to sail to arrive at Adelaide (both of which were named after Princess Adelaide of Saxe-Meininghen)

- Both Shildon and Ballarat had a Phoenix Foundry

- Thomas took control of the Kingston and Allendale band on his arrival in Creswick. The first New Shildon bandmaster, Robert De Lacy, left the New Shildon band to be come bandmaster at Allendale in England.

- When Thomas Bulch left New Shildon behind, he probably bode farewell to his fellow composer and former bandmate George Allan, later to find himself in the employ of another George Allan in Melbourne.

These examples are but a few of the coincidental connections from place to place that I have spotted along the way, which should lead me to realise that things aren’t always what they seem at first glance. But on this occasion “Whitworth” had already become one more of the missing marches of place names of County Durham. This may not have been helped by the fact that I’d recently been helping Steve Robson out with a youth band concert at Ushaw College wherein a collective youth band drawn from regional brass bands were performing his “Music Through the Ages” suite which includes a piece centred on Whitworth entitled “The Honourable Robert Shafto” which incorporates, deliciously (if that’s not too daft a descriptor) strains of the melody from “Bobby Shafto”. I just imagined that Thomas Bulch, the clever fellow, might well have done the same.

As I often do I’d shared the news of the find with Eric, before casting a speculative Tweet entreating anyone who might have “Whitworth” to make themselves known (not that we have many readers though that particular channel – ours is a relatively specialist interest, and for anyone who may well be reading this, thanks). Eric duly introduced his common sense corrective intervention shortly afterwards, knocking my own theory off into the long grass.

Above: Whitworth Hall, seat of the Shafto family, and NOT it would seem the inspiration for Robert Malthouse’s “Whitworth”

Firstly, and extremely importantly, Eric gave me eight examples from 1891 and 1892 of other performances, by the Ballarat and Sebastapol Bands and Horsham Borough Band, of “Whitworth” where the composer is named as R Malthouse. There don’t seem to be any others naming the composer as Thomas Bulch. That in itself, though pouring a bucket of cold water on my excitement on finding a supposed new Bulch title, didn’t dampen my enthusiasm for my theory. Reason being that R Malthouse is Robert Malthouse, one of the four Malthouse brothers that once played in Thomas’s New Shildon Temperance Band in England, and whom had emigrated before Bulch and thereafter persuaded him to join them. Surely Robert would have known the Whitworth estate. That at least one of the Malthouse brothers composed was something Robert Pattie had made me aware of in the past so it was nice to put a title to Robert’s name. I’d be intrigued to understand whether his old friend Thomas Bulch helped or advised him in any way.

But of course, Eric also kindly advised me that there is another Whitworth I had not been aware of, let alone considered.

Whitworth, Robert Percy.

The following was published in Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 6, (MUP), 1976

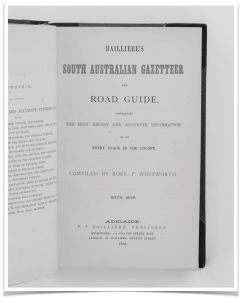

Robert Percy Whitworth (1831-1901), journalist and author, was born at Torquay, Devonshire, England, son of John Whitworth, engineer, and his wife Ann, née Dawson. He was brought up in Lancashire and Cheshire and was a barrister’s clerk when he married Margaret Rivers Smith on 9 September 1854 at Manchester Cathedral. Next year they migrated to Sydney where, according to his own account, his activities included acting—he reputedly played Laertes to Gustavus Vaughan Brooke’s Hamlet—and horse-breaking in the Hunter River district. He joined the staff of the Empire in Sydney and later began several short-lived magazines. He became a riding-master but returned to journalism after a severe fall.

In 1864 Whitworth arrived in Melbourne after some time in Queensland, and with Ferdinand Bailliere began a series of gazetteers of various Australian colonies. In Melbourne he worked with the Age, the Argus and the Daily Telegraph and for a time edited the Australian Journal. He was a proprietor and editor of Town Talk in the late 1870s and contributed to Melbourne Punch and other magazines. He wrote several plays, one of the most successful being the farce, ‘Catching a Conspirator’, in 1867. For many years he was one of Marcus Clarke’s boon companions and in 1880 was closely involved with him in the adaptation of a political farce, ‘The Happy Land’, which satirized the government of (Sir) Graham Berry. The only surviving manuscript of the text is in Clarke’s handwriting but bears both his name and Whitworth’s. They also combined in ‘Reverses’, a comedy of manners which was never performed. Whitworth was a pallbearer at Clarke’s funeral.

He spent at least four years in New Zealand and was living in Dunedin in 1870. He was a reporter for the Otago Daily Times and as ‘The Literary Bohemian’ contributed ‘clever and witty’ pieces to the Otago Witness. Whitworth’s pamphlet, published in Dunedin in 1870, describing the possibilities of the Martin’s Bay settlement on the west coast of Otago, earned him a bonus of £50 from the Otago Provincial Council. He later used his knowledge of the Maoris to write Hine-Ra, or The Maori Scout … (Melbourne, 1887).

Whitworth was a prolific miscellaneous writer. He published successful collections of his short stories: in 1872 Spangles and Sawdust and Australian Stories Round the Camp Fire, and in 1893, with W. A. Windus, Shimmer of Silk: A Volume of Melbourne Cup Stories. He wrote several novels and edited collections of stories. He compiled a Popular Handbook of the Land Acts of Victoria, New South Wales, South Australia, and Queensland (1872), The Official Handbook & Guide to Melbourne … (1880) and the second (biographical) volume of Victoria and its Metropolis: Past and Present (1888). He wrote a cantata, Under the Holly (1865), and A Short History of The Eureka Stockade (1891), and edited and contributed to several miscellanies. His wide knowledge of life in the city, bush, goldfields and theatre is reflected in his work.

He died of apoplexy at Prahran on 31 March 1901, aged 69 and 14 weeks, almost forgotten as a writer but lamented by a few as a ‘Bohemian of the spontaneous type—not the factitious’. Buried in the Melbourne cemetery, he was survived by two sons and a daughter, all born after 1867.

Eric Tomkins believes that the piece is a tribute to R. P. Whitworth. Whitworth would have been extremely well known in the Melbourne area and across Victoria through his plays and writing. Though we have no documented evidence of a connection between Robert Malthouse, or Thomas Bulch, and Robert Whitworth, one would have to ask why even a former New Shildonian would compose a reminiscent piece about a family estate near where they were born over two decades after they left that area; the balance of likelihood leans more toward the inspiration being the passing of a prominent, possibly well loved, figure of the arts world in a place where the composer now resides. It’s far more compelling.

Eric Tomkins believes that the piece is a tribute to R. P. Whitworth. Whitworth would have been extremely well known in the Melbourne area and across Victoria through his plays and writing. Though we have no documented evidence of a connection between Robert Malthouse, or Thomas Bulch, and Robert Whitworth, one would have to ask why even a former New Shildonian would compose a reminiscent piece about a family estate near where they were born over two decades after they left that area; the balance of likelihood leans more toward the inspiration being the passing of a prominent, possibly well loved, figure of the arts world in a place where the composer now resides. It’s far more compelling.

Interestingly, like some of the music of Thomas Bulch, some of the writings of Robert Whitworth endure today and can be bought. Maybe more clues lie within, though I’ll leave that thread to chase another time perhaps. There’s more to be learned about the Malthouse brothers I’m certain, but I want to get back to the two composers at the core of this project.

Lessons have been learned – though I doubt very much that it will be the last time when I’ll be grateful for the assistance of Eric, or Robert or Brian keeping the research on the rails and heading in the right direction. In some respects an element of bad luck helped my fall in that had I first found not the article incorrectly attributing the work to Bulch, but one of the correct attributions, I may well have not gone scuttling down this particular ‘rabbit hole’. I’d still be very interested to hear “Whitworth”, and to let the people of Shildon hear it, as Malthouse is a son of the town as much as Bulch or Allan – but if I do, I shan’t be imagining the deer ranging the park there in County Durham, but instead imagining the stage or the leaves of a book and the great R. P. Whitworth.

This piece with sincere thanks to Eric.