In my last blog entry I talked about the trickier aspects of identifying compositions that were created (or so we thought) by George Allan, on account of Allan being a fairly common name (common enough for there to be more than one composer named so, and several individuals involved in banding)

But what of Thomas Edward Bulch?

Well, one thing is that the surname Bulch, is an unusual one. If you search for ‘Bulch’ alone on the Australian government’s Trove archive site you’ll find that almost every result will relate either to Thomas or to a direct relation. Those results that do not comply with that theory are rare and more often than not are down to the optical character recognition misinterpreting other combinations of characters that look like they may read as ‘bulch’.

How common or uncommon is it? The surname database website surnamedb.com offers little insight, but suggests that as a name it could be found in Kapuvar and Budapest (Hungary) in a census for skilled trades in the 1890s. It also suggests that although Germanic names were not commonly found in Hungary the name does look like it may be a derivative of Bulck which was a German surname first recorded in Hanover in 1350 and believed to have originated as a nickname for a large, or small, person.

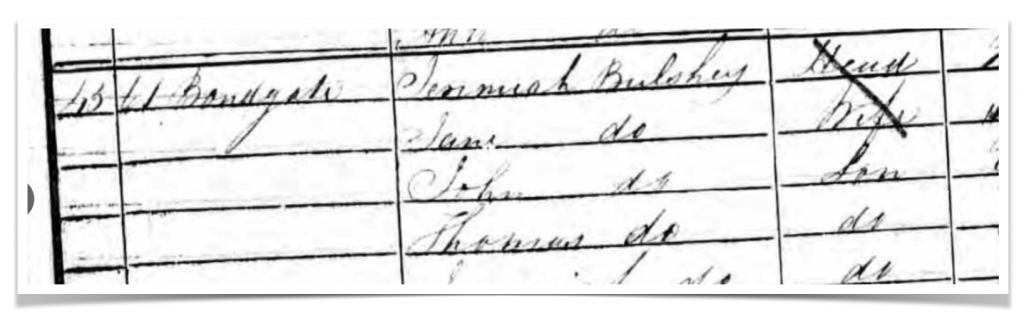

There is evidence in the Bulch family history, explored in some depth by T. E Bulch’s Grandson, Eric Tomkins, that suggests that the family name was not static, so that this theory of it having evolved seems likely. The census of 1851 has the family name of T. E. Bulch’s paternal Grandfather as Jeremiah Bulshey, a gardener.

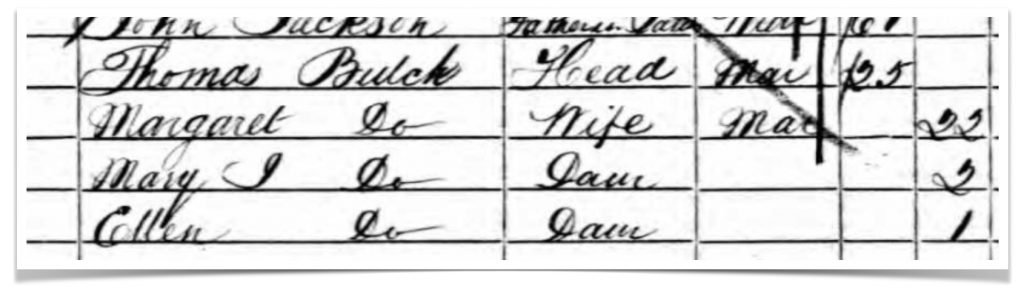

Whereas just 10 years later in 1861 Thomas, working as an ‘Engine Feeder’ (or fireman) has married Margaret Dinsdale and is head of his own household also in Darlington, with the family surname being listed as what ancestry.com understandably interprets as ‘Bulck’ (though this may be an error in handwriting)

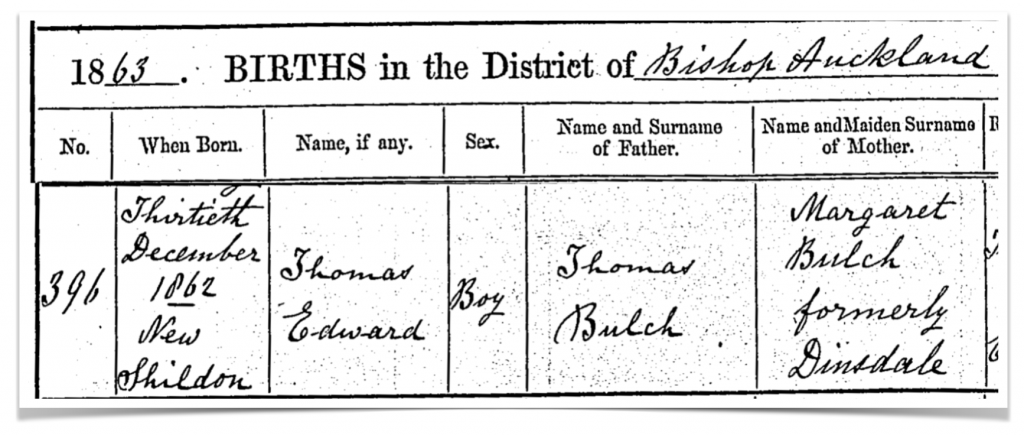

In any case, whether the family did temporarily use ‘Bulck’ or not, by the time Thomas Edward was born, in December 1863, Bulch, as is shown on his birth certificate (below), was firmly established as the family name and all records for any of the family members after this point maintain it.

In any case, whether the family did temporarily use ‘Bulck’ or not, by the time Thomas Edward was born, in December 1863, Bulch, as is shown on his birth certificate (below), was firmly established as the family name and all records for any of the family members after this point maintain it.

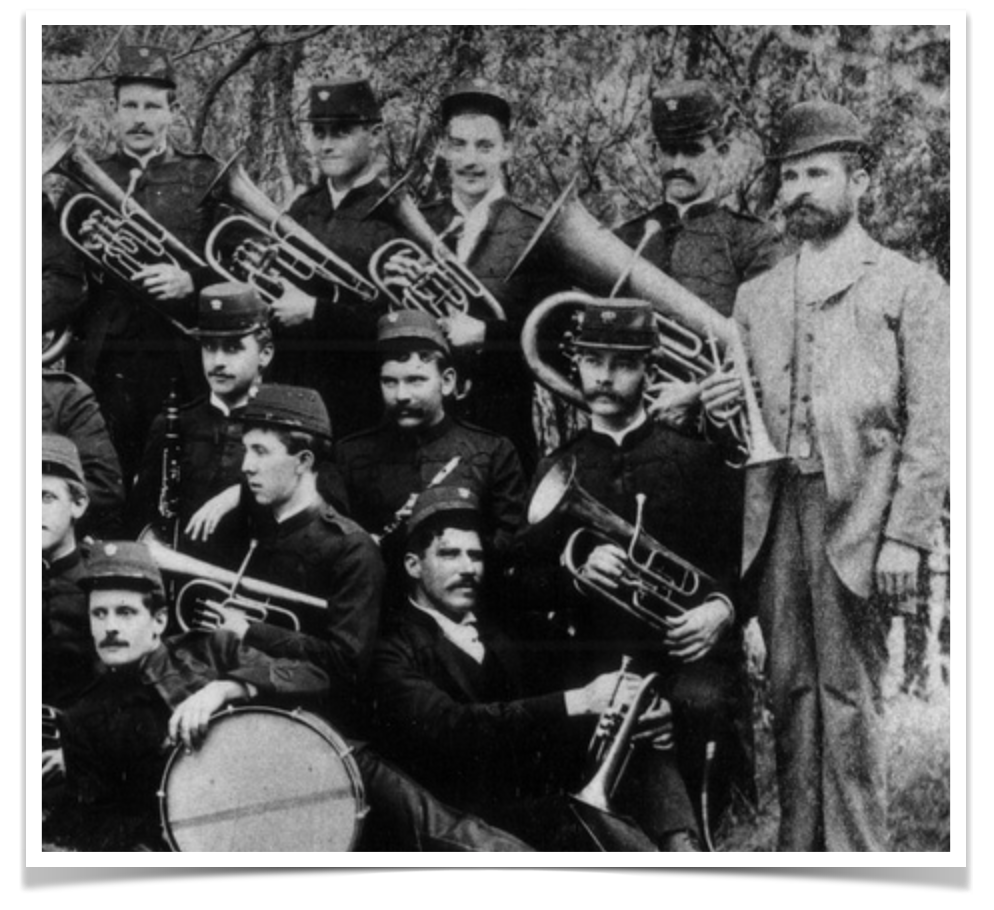

The ‘German sounding’ nature of this surname was occasionally picked up on by writers, and Thomas’s customers. For example a piece in the Ballarat Star of 1884 proclaiming his arrival to take over the Allendale and Kingston Brass Band reads “and like all German artists, he possesses a wonderful command over his instrumentation on which he performs”. This misunderstanding was to particularly give him difficulties during the Great War 1914-1918 during which locals referred to his music shop as the “German Music Shop”. According to the family history, around that time the authorities investigated his nationality and soon proved him to be of British origin.

So you would think that would make it easy, that our composer by good fortune had such a relatively uncommon name, making it easy to locate references to him in documented evidence? It most likely would be, were it not for one slight complication, which was that T. E. Bulch chose to create under a variety of different ‘noms de plume‘.

There may be many reasons for this, but the most commonly cited one is that Thomas was so prolific with his composition work that he felt buyers browsing through the sheet music in store would be fed up with seeing his name. Eric Tomkins wrote in his family history that his relative Lily Tomkins, who had been living with the Bulch family had advised him that:

“It was possible for a band’s programme to include a number of his compositions as he had written under many pseudonyms. This had been done to increase his music sales, as bands would select music of different composers for their programmes.” (Eric Tomkins)

According to T. E. Bulch’s Son-in-law, Charles Tomkins, it was possible that Thomas had used as many as fifty pseudonyms or more, and of these only a few are known for certain by family members or those who have studied his life and work. In terms of the names used, we understand from the same source that Thomas was clever in wordplay, turning words around to form new names. Why he chose certain names for certain pieces is unclear, but there do seem to be hints of themes that fit with the different alter-egos, some seeming to prefer the pianoforte to creating full band compositions (though in many cases both a band, and piano variant of each piece are available).

A number of known alternative identities for T. E. Bulch are:

- Henri Laski

- Godfrey Parker

- Pat Cooney

- Carl Volti

- Theo Bonheur

- Eugene Lacosta

- S Redler

- Charles Le Thierre

It was under the name of Godfrey Parker that Thomas Edward Bulch created the composition ‘Craigielee’ which would, via the ear of Christina MacPherson, be adopted by ‘Banjo’ Paterson as the tune for ‘Waltzing Matilda’ – illustrating that without understanding the pseudonyms of T. E. Bulch it’s unlikely that we would ever really understand his full contribution to the Australian music scene.

However, how do we determine exactly which pieces were Bulch’s. If there is no available evidence to prove that a named person existed in the physical sense it does not mean that they didn’t. It could just be representative of a person who kept a low profile. Similarly if you can ‘prove’ that a name was a non-physical person, how do you then tie the identity to the correct owner? This is something I suspect we will never be able to do for Thomas unless some document of his comes to light where he has conveniently documented it all, which would be unlikely. His cryptic approach was not so much a puzzle for generations to come, as a commercial marketing tool to try to ensure that through his hard work he could continue to make a reasonable living as a musician, teacher, bandmaster and composer.

To add to the difficulty of the pseudonyms, Thomas occasionally settled upon pen names that were also being used by another composer elsewhere in the world – which then presents the challenge of knowing that when you find a piece, you then have to determine which of the two possible composers it originated from. In a recent piece of correspondence, Eric tells me of Theo Bonheur:

“It was some years ago when I questioned my father on the pseudonyms my grandfather used, Theo Bonheur was mentioned. I later found out that a Charles Rawlings had used that name also. I wrote to the British Library and found this was correct. I also sent a front page of music which I believed was by my grandfather for their information their reply was that it was unusual for two people to hit on the same name.” (Eric Tomkins)

Another interesting case is that of Charles Le Thierre. In the family history of T. E Bulch this name is listed as a pseudonym and a number of pieces believed to be by Bulch as Charles Le Thierre are named. The Australian government’s ‘Trove’ site also cites that Charles Le Thierre is a pseudonym of T. E Bulch. However a quick search on Wikipedia (however dubious, or reliable, a reference you may feel that to be) reveals a belief that Charles Le Thierre “(also known as: Le Thiere or le Thière; born: Thomas Wilby Tomkins) (Islington, 1859 – ?, 1929) was a British composer, arranger and flautist. He was the son of a goldsmith and jeweller Thomas William Tomkins and his wife Eliza Tomkins, who had a store and company in Clerkenwell.”

Wikipedia goes on to say that “Le Thière is described by Henry Macaulay-Fitzgibbon (1855-1942) in his book The story of the flute (1913) as an extraordinary piccolo player, who also played the flute with lesser success. Also in the book First flute (1968) by Gerald Jackson (1900-?) he is described as a musician without a permanent position who composed or arranged to feed his drinking habits. Despite this, and before he fell on hard times, he composed pieces like L’oiseau du bois and Danse de Satyrs, both for piccolo. He also wrote The Royal Tour for piano solo and his Sunrise on the Mountains and Village Life in the Olden Times were introduced by John Held in the United States in 1890 for his orchestra. Le Thière also arranged the well-known The Punjaub March by Charles Payne (1887) for orchestra and wind band. In an undated letter his address is given as care of Potter & Co, 36-38 West Street, Charing X [Cross], London WC2, in which Le Thiere mentions he is 70 and in the workhouse. For some time he may have lived at 26 Tonman Street, Deansgate, Manchester.[3] Presumably he died in poverty.”

There is certainly a belief here that Le Thierre is someone else entirely. Looking at many of the available digitised pieces that are named as being by Bulch they do seem to be most commonly published in London rather than Melbourne, or Sydney, Australia. The dates of his life given suggest him to be very much a contemporary of Bulch, but it’s his born name that piques my interest the most. Thomas Wilby Tomkins – the same surname as Thomas Bulch’s Son-in-law, Charles, (and of course Grandson, Eric). Is there more to this than meets the eye? That’s something we can look at perhaps.

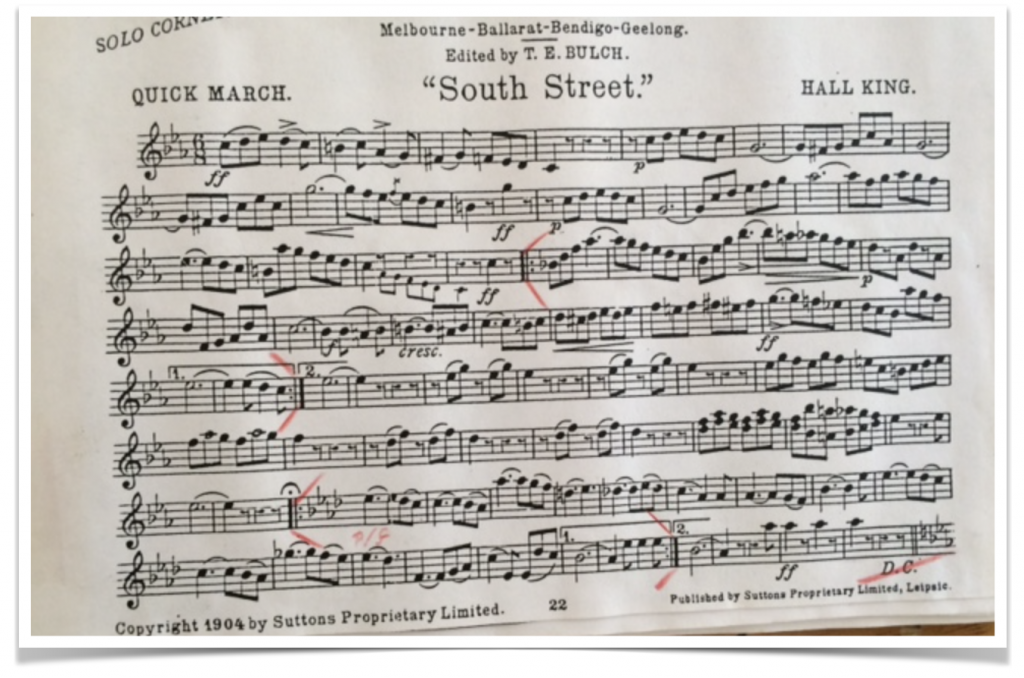

Another recent example that Robert Pattie highlighted to us was for a piece called “South Street” attributed to Hall King. As Robert points out, this March has all the fingerprints of Thomas Bulch’s arranging and his name as editor at the top. We know T. E. Bulch composed “South Street Parade”, and that South Street is a key area of Ballarat. It is also printed in Liepzig, as much of Bulch’s other work was (as he recognised that the German printers were at the cutting edge of music print technology at the time). The name ‘Hall King’ just doesn’t ring true for some reason. When I asked Eric, he theorised that it could be a reversal of King’s Hall, though there doesn’t seem to be a relevant connection in that. It may well have been a genuine person.

So for now some things remain, just a little, mysterious. But as you can see and appreciate there is much that will keep us busy in the coming months. Personally I suspect that the most difficult decision is going to be knowing when to ‘draw the line’.