One of the things we always hear about George Allan is his excellence in the brass band contest march format. He’s the gifted amateur “march king.” you say. It’s certainly what he’s best known for nowadays – and when I say ‘best-known’ I mean ‘just about only known for.’

We know that the brass band movement kept on moving throughout George and Tom’s time and some of their music became dated even while they were alive. Yet not everything. In George’s case, pieces like “The Wizard”, “Knight Templar” and “Senator” sound as bold and lively now as they did in the first two decades of the twentieth century when they were created.

I’d argue, though, that sometimes it’s not such a bad thing for a piece of music to sound dated. For example if you want to peer into the past and get a sense or feel of the times. Sometimes, though, you just want to look for those pieces that sound as good now as they did the first time they were played. Especially if, as we are, you’re trying to curate a programme for a concert to tell the world the story of the music’s creators, and both impress and entertain an audience to convince them that two special talents arose in this town. In a lifetime collection of some 450 compositions and arrangements, though, many of which have not now been heard for a hundred years, how do you go about finding the pieces that create that effect best.

This brings us to “Gabriani.” Have a listen.

Now I’d been curious about the overture “Gabriani” from the moment that Brian Yates brought it to us. He’d managed to find a full set for sale online and donated it to us. I’d seen the name through the research I had been doing, trawling newspapers looking for band programmes that included George Allan or Tom Bulch’s work. In those early days I’d maybe found about 500 references in total, but even then “Gabriani” by Allan was one of the most frequently mentioned. As I write this a few years later I have now identified 111 occasions at which “Gabriani” was played in the United Kingdom, Australia and New Zealand in the period between its creation in 1899 and 1954. Of course that isn’t to say it’s only been played 111 times. Most times a piece of brass band music was played by a band it was never reported or mentioned in the press. So to have found it mentioned at 111 separate occasions suggests that it was played many, many, more times. Which in turn suggests something else.

On Sat 8th July this year I went to the Durham Miners Gala – an occasion that was, we’re told, particularly fondly thought of by George Allan, who found it an inspiration to create new music. Being there, and seeing so many bands in one place with all the silk banners flying high over their heads in the sunshine, you can see why. I know we’re in different times, but I like to go and put myself in those few hours in his shoes. Of course that too is a day that’s all about he marches. If you stay on one spot for long enough you’ll hear band after band playing “Slaidburn” and “Death or Glory” as they march past. But why always those.

It could be because they are relatively easy to play, especially on the march; or because they are part of the traditional repertoire of such occasions. They are not challenging pieces. But there’s more to it than that I’m sure. They are effective, stirring and conjure up a magical essence of times past in a way that can still stir the common soul today. There are few among us, fans of brass music or those that prefer rock, rap, or RnB but have that albeit different emotional connection to music, that can deny that they feel pulled into that sphere of wonder and sentimentality when a brass band plays an effective march. So what I’ve been looking for among George Allan’s work is something similar that can stand alongside his best marches, something whilst not ‘brilliant’ in the sense of what top bands consider to fit that word nowadays, but effective such that we can say “Aha, so there was more to the man than his marches.”

I has a feeling that because bands had chosen to play it over five decades, there might be something of that quality to it. Yes, some of the bands listed are only mentioned playing it once. The first I have seen reported were the Stokenchurch Temperance Band, who aired it the day before New Years Eve 1899 hours before the millennium and the new dawning of the 20th Century. Others though played it time and time again such as the Montrose Town Band (still going today) who played it first in 1913 just a couple of years after their having been founded, and stuck with it until at least 1954.

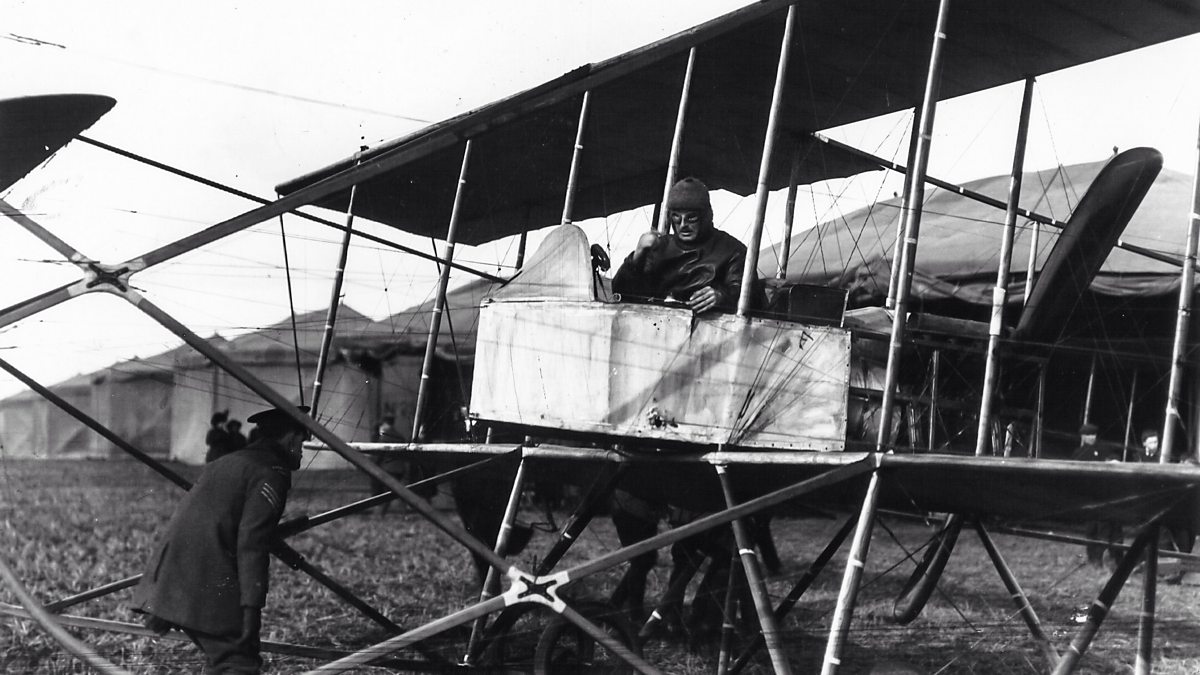

It was this connection to Montrose that was the reason I chose the image for this blog post. Montrose was the location of Britain’s first military airbase, which was opened around about the time that the Montrose Town Band are first reported as having played “Gabriani”. The featured photograph was taken at the base in the same year it opened, 1913. Interestingly that base, originally created for the Royal Flying Corps, is still there today as the Montrose Air Station Heritage Centre.

I had a feeling this might just be the kind of piece I was looking for. Our collection was spread out in a few locations prior to this year, and I didn’t have “Gabriani” here – but we brought the collection together in one place this year to create a consolidated archive – and I only recently found a little time to copy it all into Sibelius to try out and hear.

Why Gabriani then? What on earth is a Gabriani? What might that name mean to George Allan?

Let’s consider a few references George might have been aware of. Gabriani is certainly a surname. As a word it doesn’t seem to translate from any language, and it looks like a name so probably is one. In May 1746, during the War of the Austrian Succession (Europe almost being perpetually involved in now long forgotten wars, there was a General Gabriani, serving on the side of the Austria against the Spanish, who was instrumental in thwarting a Spanish ambush that took place in the vicinity of Codogno. He was hardly one of the household name generals of his day, let alone George’s time. The American Register of 28th Nov 1903 makes mention of an actress named Mademoiselle Gabriani acting and signing in Offenbach’s “Bonne d’Enfant” in Monte Carlo, wherein she was reportedly to be congratulated for scoring a success in both capacities. So it appears to be derived from someone’s surname – but whose specifically I doubt we’ll ever know. As a surname, Gabriani appears to be very rare, appearing in Italy, Switzerland, Germany but also in Brazil and Argentina. A search of genealogy websites suggests that there were no people living in the United Kingdom with that surname during George’s lifetime, though there were some with derived surnames such as Gabrian or Gabrien. I haven’t been able to find a composer named Gabriani, whose work might have been the inspiration for this overture. It’s something of a mystery.

Whatever the inspirations, I think this piece of music to be a pleasing one, and certainly worthy of inclusion in a concert. Compared to the other Overtures by Allan that I have heard, such as King Edward, this one holds together well, has a few classic George Allan qualities to it and is memorable in part. It might not have the scintillating brilliance of Knight Templar or The Wizard, but then not every piece was created to test a band to its limits. I’m pleased we have it in our collection.