When I think of the Victorian era, which came to a close almost 120 years ago, it’s tempting to consider how our perception of the importance of time has changed.

We currently enjoy an era of near instant gratification where much of the information we need can be summoned to our presence within seconds; where goods can be ordered, wherever we are, that then reach our doorstep the very next day; where we can communicate face to face in real time whatever the distance; where world events are served up to us almost as they happen.

For those working in creative industries the powerful, increasingly digital, tools exist to enable us to hasten the flow of ideas becoming reality. 3D printers enable even physical objects of some complexity to appear without the need to engage a manufacturer. The main overhead in the creative process now is the time you choose to spend developing your idea, and perhaps the time taken to determine whether you consider it finished. After this, the logistics of providing digital products to a customer are generally simple. With the right software, sometimes a little hardware (depending on the task), and a modicum of know-how, any person with musical knowledge can become composer, recording artist, publisher, printer and distributor, controlling as much of the end to end chain as they care to involve themselves in with significant ease.

Likewise, in the field of travel, we can traverse the globe, by air, reaching a destination at the opposite extent while spending less than a day actually travelling; or make a journey by car between the furthest extents of Great Britain in a similar period of time. Modern manufacturing and supply chain processes operate on a ‘just in time’ principle where the right part or product appears just when it is required so that no time or space is wasted storing or caring for it, either side of that moment. Time is money. Time is everything.

As wonderful as all this is, it does seem as though our expectations around time have adjusted with each improvement so that no matter how quickly something happens, after a short while, it never seems fast enough to be perfectly satisfying. The supermarket queue, where interaction between the assistant and customer has either been eliminated or else minimised for efficiency, a palpable tension is still evident whenever a bar code proves unreadable. On the sofas, buses, trains, park benches and pavements of England, fingers twitch irritably as patience is stretched to its limit by a few seconds of digital ‘buffering’.

Examining Victorian practice, simply thinking about how long certain things might have taken also generates a hint of that frustration. In our case, I am thinking of the printing of music.

One thing that Thomas Edward Bulch, and then later George Allan, did was publish their own compositions. Not all of them, but many of them.

The first published works of both composer/arrangers were produced and distributed by Thomas Albert Haigh of Anlaby Road in Kingston-Upon-Hull in his Amateur Brass and Military Band Journal. This would have required Thomas or George to submit their handwritten manuscripts of all the parts to the publisher. Presumably, unless pieces were commissioned by request, there would follow some process of acceptance or refusal, and then might follow a lead time while an available space in an upcoming journal is sought and scheduled. Then the publisher would either have arrangements with a printing company to engrave and print them, or as was later the case with Haigh, would have a printing works of their own at which the sheet music might be printed.

We can see from the availability of published requests for tender that Haigh had a print works and warehouse built explicitly for printing music at Albert Road near his home. We also know he had printing equipment as there are newspaper advertisements of him selling second-hand printing machinery and equipment, presumably as he replaced it with new gear. The printer would have to correctly interpret the handwritten manuscript and then translate that interpretation to an accurate and clear print. Mistakes could prove costly. Taking time to check proof copies of the print, were that an

In time both composers, taking a lesson from bandmaster composers before them, would attempt to bring to life their own brass band journal. Just as Robert De Lacy, the New Shildon Saxhorn Band’s very first bandmaster, had set up his London Brass Band Journal, Thomas Edward Bulch too created his Bulch’s Brass Band Journal and Intercolonial Brass Band Journal. Much later in his own

Assuring the printing of a brass band journal looks to be a very different commitment to printing compositions individually as they emerge. It would have been perceived to be worth it though as a journal usually had committed subscribers. A journal also usually would have a defined frequency. Typically this would involve being printed and advertised as being made available from music sellers on the first of each month. Making that happen required a significant amount of planning.

One other aspect of this that united both Thomas Bulch and George Allan is that they, perhaps through their dealings with other music publishers before striking out on their own, had learned of the importance of the quality of

It was by no means the only option available, but nonetheless, both Thomas, and later George, arrived at a similar conclusion that they would send their compositions to Leipzig to be printed. Thomas Bulch, probably influenced by what he saw from the other publishers in Australia, or by what he saw in music he bought himself, chose to have his publications printed by a company which was probably the largest in Leipzig; the print works operated by C G Röder.

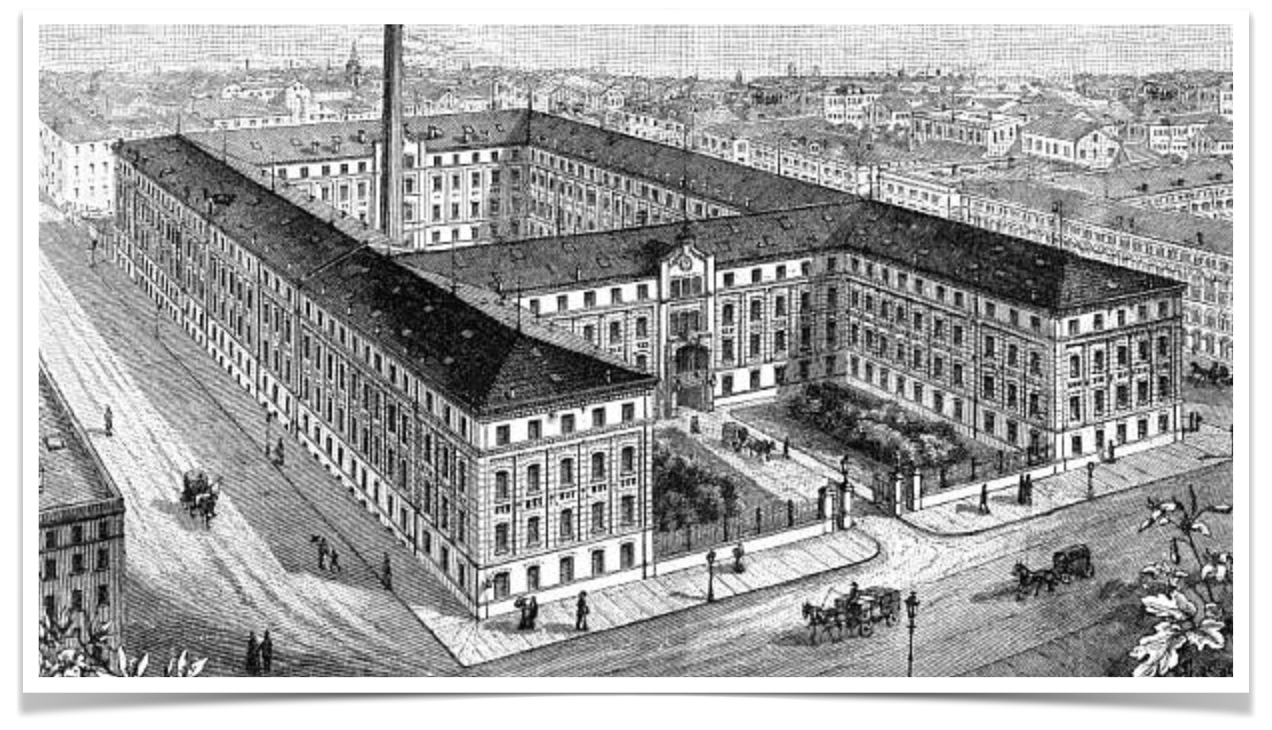

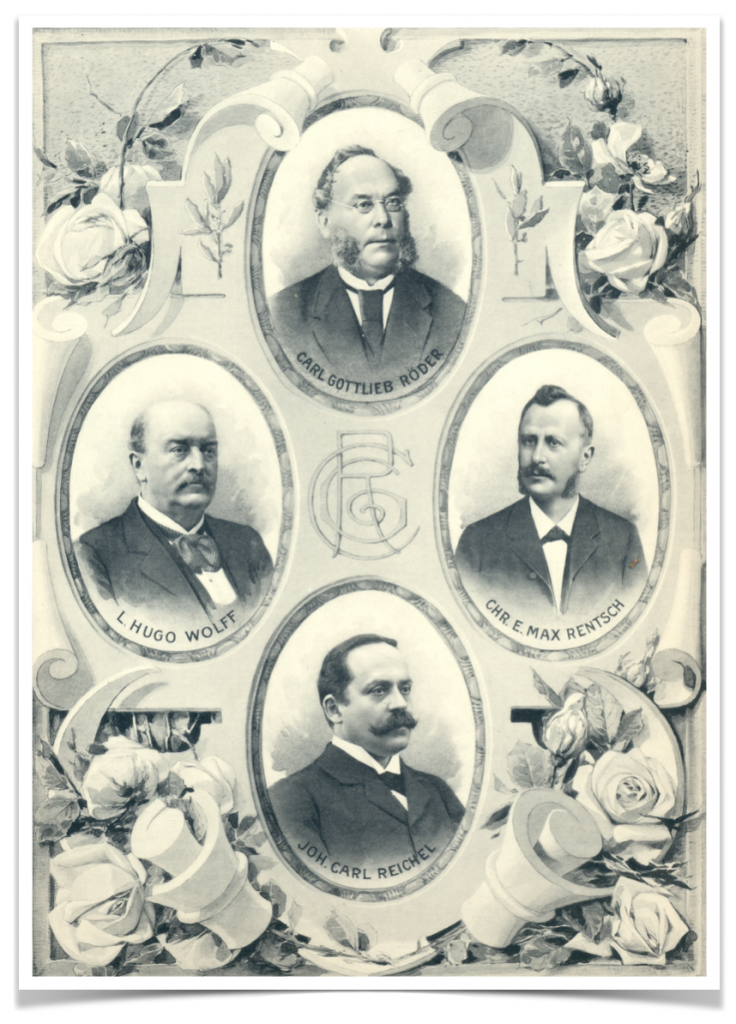

Carl Gottlieb Röder, the son of a Leipzig baker, became a music engraving apprentice after leaving the army aged 26 in 1838. By 1846 he had started his own business on Leipzig’s Holzgasse using only a small hand-operated press. Within seven years he had bought out another music printing company in the city and was employing 36 people at their new premises at the Tauchaer Strasse where the business stayed until 1866. By 1871 at even newer premises on Dorrienstrasse the company was annually producing annually 80 million sheets of lithographically printed material and 5 million from engraved plates. In 1873 construction of a new long-term home for the printing business, depicted in the featured image for this post, was commenced between Dresdner Strasse and Taubschenweg next to the Gerichtsweg. This would be expanded over the following decades and would be where T E Bulch’s music was produced.

Carl Röder himself retired in 1873 and was succeeded in running the business by his son-in-law Hugo Wolff-Röder and another son-in-law named Christian Erdmann Max Rentch, who closely followed his policies for

Each of Thomas’s compositions would have to be first imagined and then written out by hand. Works by others that would be selected to be included in his journal, would need to be checked and tested, editing the music where necessary. As much as possible we believe that the finished manuscript would be tested with a band; where the reputation of the publisher hung on the quality of the journal there would probably be little point sending a piece to print until the creator knew how it sounds. With no composing software or recording equipment to hand, a good working knowledge, as Bulch had, of the pianoforte as a polyphonic instrument would be a useful tool. Then being a bandmaster with a band at your disposal would undoubtedly have helped.

With the creative, and proving, process complete, the handwritten manuscript would have to make a long voyage by steam-ship to Europe from where it would make the long journey overland to Röder’s works at Leipzig. Then the bundled printed product would be dispatched in the opposite direction. The whole process would take weeks and would require significant planning and patience.

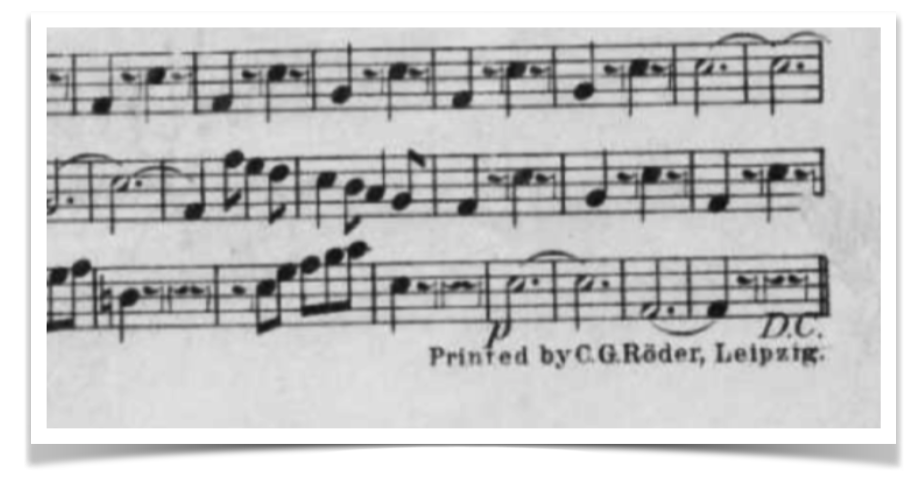

For Thomas Bulch’s customers seeing that the music was printed in Leipzig, Germany served only to enhance the perception of the product initially. From news published after Bulch’s arrival in

The quality of the Leipzig produced sheet music did have, without a doubt, a crispness and clarity to it that makes it, even now, very clear to read. The German printers also had a reputation for faithfully and accurately representing the music in their translation from hand-written manuscript to printed note. This was an aspect greatly appreciated by the composer. Their reputation grew, or diminished, as each composition reached the music warehouses depending upon how they were received by the bands that would play them. Anything that would be a good influence on that reception could surely only be a good thing.

The printing business itself gradually improved in quality and efficiency over time, and the German printers were keen to stay at the cutting edge of technology. By 1896 all the machinery in the Röder plant was no longer powered by transmission drive belts, but by electric motors powered by a

We are still working on understanding the timing of the publication of George Allan’s own brass band journal, though we believe it was much later than Bulch’s. This was probably a matter of opportunity as much as will, for as we know George was employed day to day for long working hours in the blacksmith’s forge at the railway wagon works in New Shildon creating the miscellaneous hardware essential in the assembly of the wagons. For George, it would be more manageable to engage with the existing publishers in an already crowded and competitive market, even if it did mean that the returns were much reduced after the publisher had extracted their share of the revenues.

After having been published by Haigh for some years it is believed that he was then published by Fred Richardson in the Cornet band journal (works from that period later being acquired by Wright and Round as they bought out Richardson at his retirement) and perhaps only then after a flirtation with what looks to have been a short-lived Standard Brass and Military Band Journal centred on Boston, Lincolnshire, did he start with his Popular Brass Band Journal.

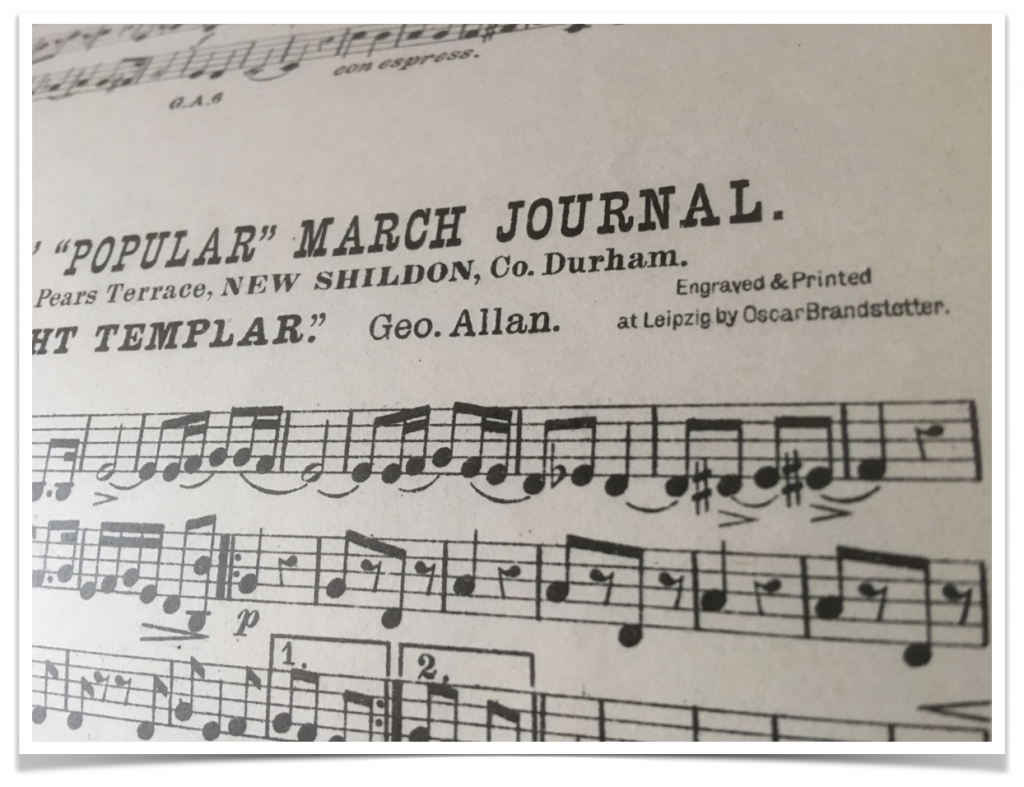

When the time came for him to start the Popular Brass Band Journal, and to decide where his work should be printed, he too turned to Leipzig. Though not to the C G Röder printing house as Bulch did, despite the convenience of their having a London office. George Allan chose to enlist the services of the Oscar Brandstetter printing house that was located in the same district of Leipzig as C G Röder.

This was most likely due to the fact that prior to starting his own journal, George’s pieces were published in Richardson’s “Cornet” band journal and then the “Standard” band journal, both published from Boston, Lincolnshire, and both of whom had used the Oscar Brandstetter works to engrave and print their music. It’s interesting to note, though, that some of George Allan’s pieces, such as The Belle of Bohemia were published by Wright and Round in their Liverpool Brass Band (& Military) Journal which was printed, like Bulch’s works, by the C G Röder print house.

Of George Allan’s journal, only the earlier pieces appear to have been printed by Oscar Brandstetter. This, most likely, for reasons that we will come to in a few moments. It’s unclear where George’s later pieces were produced as they bear no printer’s mark or imprint, just the publisher’s name. But, the Brandstetter printed compositions do possess a more refined appearance and quality and are easier on the eye. They are very appealing. The good news from George’s perspective was that the route between Leipzig and New Shildon was by far shorter than that taken by Thomas’s compositions.

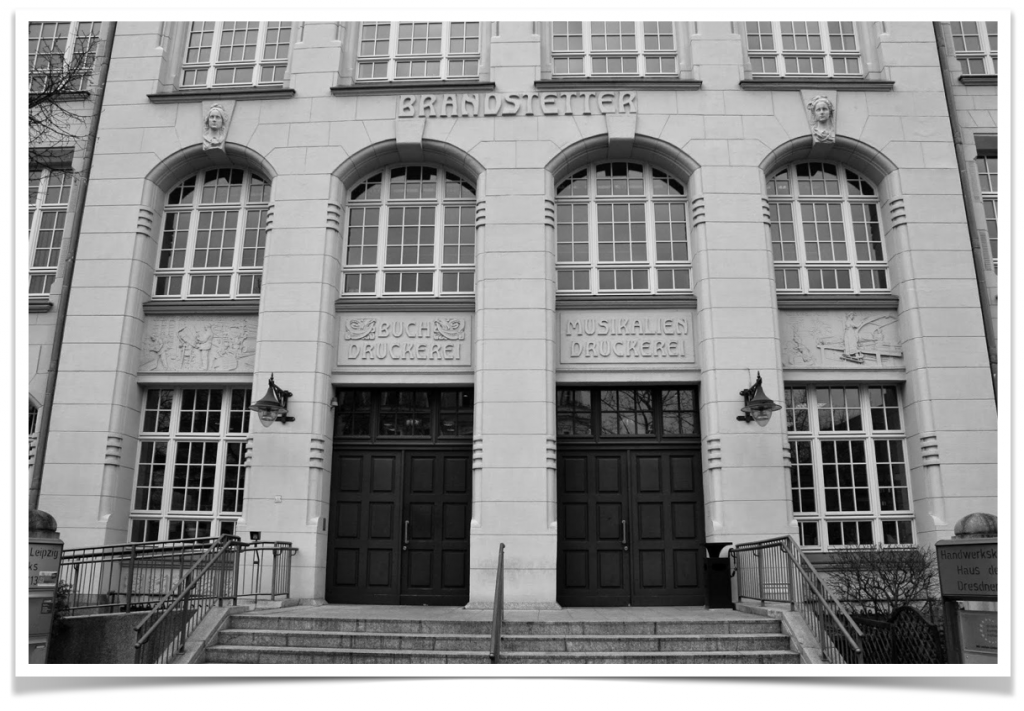

The Brandstetter print house had originally been founded in 1862 by Friedrich Garbrecht as the “Anstalt für Notenstich und Notendruck, Lithographie und Steindruck” (or “Institution for sheet music and notation, lithography and impressions”). The current owners of the company possess a printed in 1937, covering the history of the printing company from 1862 to 1937. It was bought in 1880 by Oscar Brandstetter, son of a merchant and publisher, Friedrich Brandstetter, who was the

According to Udo Amm, an employee of the Brandstetter company in its current form, as a young man Oscar Brandstetter had spent a few years in England. Consequently, he was fluent in English, and since 1875 had been a naturalised British subject. For composers in the English speaking nations, this would have made him very easy to do business with.

Music printing, according to Otto Säuberlich, technical director of the Brandstetter company from 1875 to 1928, was an interesting market for printers because firstly music and its notes are international, thus facilitating international business contacts; secondly it is technically difficult with low production volumes compared to book printing making it a niche market with less competition; thirdly customers once acquired usually stay with a music printing company, especially because printing plates stayed with the printers for possible further printing. Leipzig overall had a long tradition in printing and the book trade in general

In the years that followed the Brandstetter company developed into a large and successful graphics printig company. Udo Amm advised us that what made Oscar Brandstetter Druckerei one of the greatest and finest music printers was the excellent and clear-sighted management by Otto Sâuberlich and Oscar Brandstetter who always kept abreast of technical developments and introduced innovations very early. This early use of new technical developments in the printing process played a decisive role in the success and appeal of the company. For example the introduction of

Other innovations followed. In 1904 a pioneering deployment of monotype setting and casting machines; in 1910 the first two colour and double-offset printing press in Germany; in 1919 the first German rotary offset press; in 1920 an offset reprinting process known as the ‘Obraldruck’.

Similarly, C G Röder’s business kept up with the best in technology, expanding too into the production of printed postcards. By end 1907 the Leipzig works belonging to Röder had a production area covering 25,100 square metres and employed 1,100 people. 1913 saw Röder with offices in Berlin, Paris, London, Vienna, Budapest and Brussels; but trouble was also looming.

In 1914, following the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo by a Bosnian Serb Yugoslav nationalist, tensions that had been simmering across Europe erupted into war. This spelt disaster for both the Röder and Brandstetter companies who had built their business largely on export. The German printers found themselves on the opposing side to most of the international customers they had worked so hard to acquire. Consequently, order volumes plunged catastrophically. The Röder company was eventually to forfeit their subsidiary print works in London and lost access to bank accounts. The overall loss was in the region of 3.3 million Marks. A year into the war Leberecht Hugo Wolff-Röder passed away and the mid-point of the war saw the worst business year the Röder company had experienced since its founding. Many workers were conscripted into the German army. Others were made redundant through lack of demand.

For Allan and Bulch, what was once deemed a positive quality of their arrangements and compositions in print was now a definite ‘black mark’ in the mind of the music buying public. For Thomas Bulch, as we have already explored elsewhere, the fact that his music was produced by a mortal enemy of the British Empire simply added to confusion over his own identity and, despite his two sons enlisting to fight for the Empire overseas, sales of his music mirrored the slump in business suffered by the printer. His music shop was referred to as the ‘German music shop’ and was shunned. Despite proving his detractors to be incorrect, the impact of the war on sales of Thomas’s music was to be a lasting one.

George Allan,

Whilst it’s not altogether clear to determine, one can imagine that during the First World War composers and publishers would have had significant difficulty making alternative arrangements for the printing of whatever they tried to produce in that period. The businesses that had built up the capacity to produce the music were now physically, or morally, inaccessible. The skills and production facilities elsewhere probably limited and perhaps engaged in other activity some of which may have been more critical to the war effort.

Furthermore, bandsmen of fighting age worldwide, T E Bulch’s own sons included, were also forfeited to the war effort. Unless their members were occupied in trades essential to the domestic function of a nation, depleted bands would doubtless struggle to maintain sufficient market for brass music.

The war would also impact worldwide appetite for music. Throughout the golden age of brass band music there had been a distinct thread of militarism. Bands in however smart a uniform they could afford would play pieces by composers named after notable battles, or acts of valour, or depicting the camaraderie of the military life. Though Allan’s were less so, T E Bulch’s works, perhaps through his particular involvement with military bands, included a significant number of military pieces. By the end of the Great War, which had seen man kil man on a scale unlike any other before it and in ways previously unimaginable, there was

The printing businesses of C G Röder and Oscar Brandstetter survived the Great War, but business was highly significantly impacted by it and recovery was slow. Neither T E Bulch nor George Allan, to the best of our knowledge, used the German printers again after the war.

The Röder and Brandstetter companies eventually regained peak trade in the buildup to what would prove to be the second great war of the century. During that conflict, the improvements to military technology during the intervening two decades proved even more devastating materially as well as financially. The development of longer range and heavier bombing aircraft resulted in both of the Leipzig print works being badly affected by A

Much of Röder’s printing equipment was sent to Russia after the war, but again both businesses survived in most respects though their nature changed significantly. Though the C G Röder company is no more, Oscar Brandstetter’s has evolved into one of the most noted publishers of technical manuals and medical literature in Germany.

Many pieces of printing equipment used in the printing works of Leipzig have been preserved in a Museum of the Printing Arts Leipzig, where visitors can see the processes, including those for music printing, in action. This is something we’re making arrangements to experience for ourselves in February 2019. We’ll provide an update then.